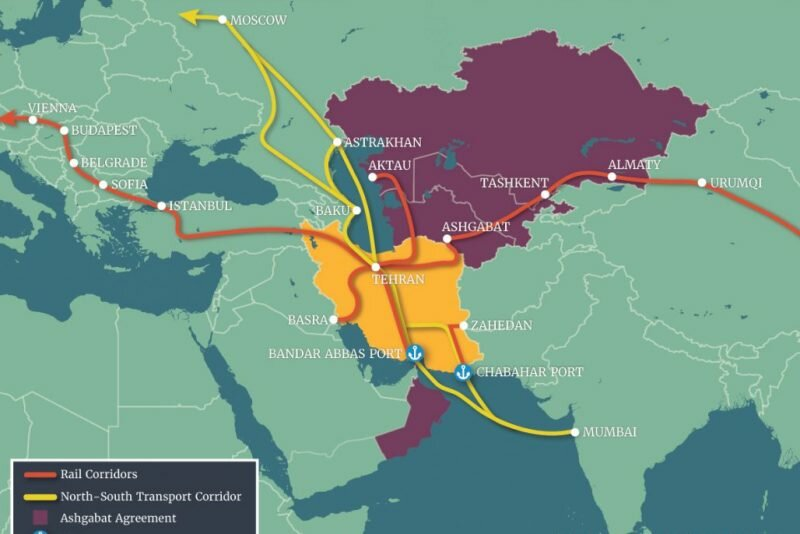

The advantages of the corridor:

- Reduction of dependence on Suez;

- Time and cost reduction;

- Alternative route for Indian goods to Central Asia (primarily Kazakhstan) by bypassing Pakistan;

- Alternative route for Indian goods to Europe bypassing Red Sea, Africa, Bosporus and traditional key ports of Europe (such as Port Said, Rotherham, Tangier, Hamburg, Genoa, Trieste, Thessaloniki, and the like);

- Pivoting Iran as a median crossroad, and hence further stabilizing it;

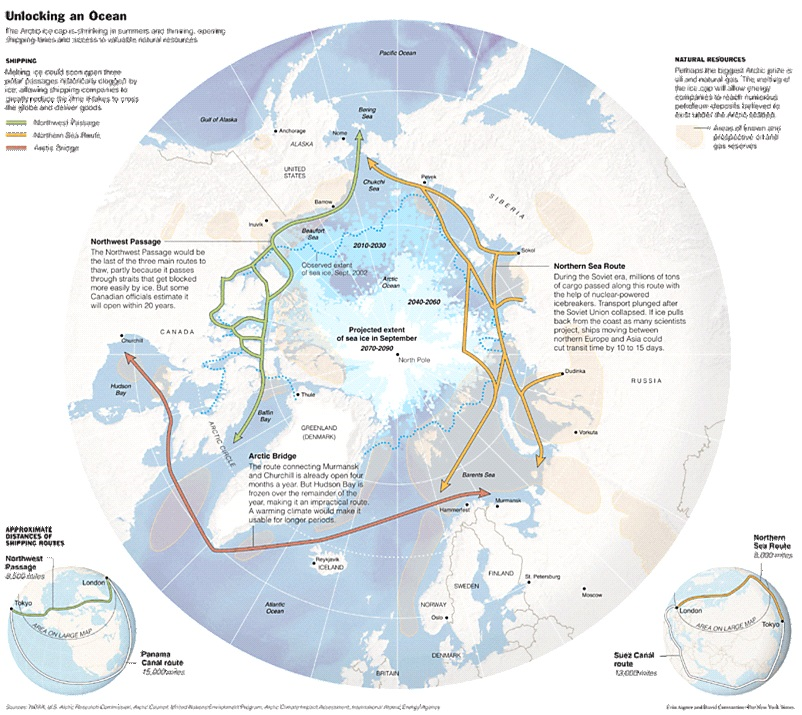

- Breaking the isolation and circumvention of sanctions for Russia, while bridging it with the Arctic bridge;

- Complete integration of the littoral states region around the Caspian Sea as a new global hub.

Bandung (1956), Belgrade (1961), Johannesburg (2023): Materialization of the Grand Visions

Hence, she noted “Today Eurasia is the axial continent of mankind, which is home to about 75% of the world’s population (see Map 1), produces 60% of world GDP (see Map 2) and stores three quarters of the world’s energy resources (see Map 3) [Shepard, 2016]. In these open spaces, two giant poles of modern geoeconomics are being formed: European and East Asian, which are tearing the canvas of the familiar geographical concept of “Eurasia” and at the same time providing opportunities for new synthesis through the construction and connection of transcontinental transport arteries.”

Past the historical Johannesburg gathering of BRICS, with the “unprecedented (post) Maastricht-like deepening (institutions’ building) and widening (massive enlargement with 6 robust either demographics or/and economies – hence larger than any of the EU /or for that matter NATO/ enlargements ever) – this grouping is the best living example of the grand idea of Tito, Nehru and Nasser’s postulated active and peaceful coexistence that came to life in Yugoslavia in 1961” – as professor Anis H. Bajrektarevic commented the 15th BRICS Summit.

How the active and peaceful coexistence is materializing itself without confronting but rather by complimenting the existing world order?

Nowadays, irreversible power relocation has begun, even if there is not a precise gravitational center. Indeed, the global order is archipelagic and “fluid”, as even the western media recently admitted. Since the Russian special operation in Ukraine, a magmatic phase started, incentivizing new triangulations and alliances, sometimes alternatives to the West primacy. Of course, the United States remains the global technological and military pivot, and NATO remains the first military alliance, but it is undeniable that the balance is evolving.

The International North-South Transport Corridor (INSTC) involving Russia, India, and Iran (in total, 13 members) fits into this multipolar-evolving context. If integrally implemented according to plans, it would make it possible to reduce the supremacy of Suez, through which about 12% of global trade transits. This project will encourage a Euro-Asian synchronization and provide an alternative to the traditional Suez route exclusivity, reducing approximately 40% distance and costs by 30%, as claimed by Silk Road Briefings.

Infrastructures have a substantial role in the growth and decline of power. The case of the Suez Canal is emblematic: it interrupted the complex circumnavigations and restored the centrality of the Mediterranean. For this reason, powers aspiring for a hegemonic role invest in infrastructural networks: China with the “Belt and Road” Initiative – Research Fellow at IFIMES/DeSSA Dr Maria Smotrytska described the shifting-balance project in her detailed analysis – while Russia and Iran with the Corridor. As a result, the project is fraught with enormous geopolitical implications.

However, these are not the only initiatives. Having overcome the internal turmoil, Algeria (as a forthcoming BRICS member) has heavily invested in the new Trans-Sahara Highway Project, 5,000 kilometers long, from Algiers to Lagos. In this way, the “republican” Algeria hopes to bypass the “monarchical” Morocco and, finally, the Strait of Gibraltar. The name “African Unity Road” testifies to the socio-geo-political significance.

The Anglo-Saxon thalassocrat powers – the authors argued – could not withstand the impact of such vast empires, with young and numerous populations set off for industrial and infrastructural development as well as with boundless natural resources. For this, it is essential to control the Rimland and try to hold back the momentum of the empires, fighting one at a time: once Russia, once China. The containment policy against the Russian giant also derives from these reflections.

They were well-justified fears. At the time, Russia, which had already become a pivotal protagonist on the European scene since the Napoleonic wars, had expanded into the Caucasus and Central Asia. Soon after, that very theatre scored significant rates of economic and demographic growth, primarily thanks to the Trans-Siberian railway and the consequent colonization of Asian Russia. The Czars also aimed at the seas, the Indian Ocean, and the Mediterranean. For that same reason, Crimea has historically been crucial in Moscow’s strategies.

Analyzing the complex geographical composition of the Euro-Asian mass in The Geography of Peace (Harcourt, Brace, 1944), Spykman notes that the seas arranged in an arc all around has facilitated the development of the coastal areas, while the more inland areas have always remained disconnected and without reliable communication routes; this prevented full integration. As a result, communications almost always took place with sea routes. However, there are infrastructural interventions that can break the setback of geography.

First, the Russian-Chinese integration is already a reality: trade could reach a value of about 200 billion USD by the end of 2023. Furthermore, China is a privileged end market for Russian resources, but Russia is also a relevant market for China that could compensate for the loss of shares in Taiwan and the United States with Russia.

Similarly, trade between Russia and Iran quadrupled in 2022. Interestingly, trade between Iran and the Caspian littoral states amounts to 5.54 million tons worth $3.03 billion (according to Mak A. Bajrektarevic’ book ‘Caspian: Status, Challenges, and Prospects’).

Source: Public Domain

After the capitulation of the European powers in 1939 and 1940-41, the USSR had to withstand an overwhelming shock force and was initially forced to retreat. As the Soviet military and industrial complex came into full swing, the corridor, especially in its initial stages, had a greater importance than is generally attributed. The corridor was the only reliable channel to support the USSR as the Nordic and Arctic routes towards Murmansk and Archangel were controlled by the Nazis.

After decades, the project was relaunched in the early 2000s and is listed as a priority by the countries’ governments. The corridor responds to the needs of the three major players involved: access to the Indian Ocean and the Gulf for Russia interrupting isolation, internal infrastructural strengthening for Iran – the country will become a pivotal crossroads of rail, road, and sea routes – and projection towards Central Asia for India bypassing Pakistan, which has become a key-country for China.

In addition, the initiative also has beneficial effects for all the other regional players: the former Soviet republics, Azerbaijan – the port of Baku is becoming an increasingly important hub (over 6.3 million tons of cargo in 2022) – and Armenia, but also the GCC (Gulf states), which are now the protagonists of a cautious and attentive policy to redefining the global politico-military and energo-economic balance.

Current forecasts predict the doubling of freight volumes from 17 million tons per year to 32 million in 2030. The completion of the project would also lead to a shift of the trade and transit axis towards the heart of Central Asia.

Source: Smotrytska (2022), the pre-C-19 World’s Crude Shipments Levels (UCL Energy Institute, 2019)

This canal is crucial in Russian Iranian commercial exchange: an estimated 35 merchant ships passed through the Volga-Don passages in 2021 (annual average), but this number grew to 50 in 2022 (42% more). However, despite the growing importance of global trade, the intermodal capacity of the ports on the Caspian Sea is still limited (Mak A. Bajrektarevic’ ‘Caspian: Status, Challenges, and Prospects’). At the same time, the interconnection between ports and railways in Iran is still lacking, but the two partners are willing to invest.

Finally, it is very complex to scratch the supremacy of Suez, especially after the doubling. The data show constant growth: from 2011 to 2016, over 16 thousand ships passed through Suez, while in 2021, over 20 thousand (more than 56 per day), as reported by the Suez Canal (SCA). In 2021, about 1.27 billion tons of cargo were shipped through the canal. Therefore, Suez and Panama remain the fundamental facilitators of modern navigation.

Nevertheless, besides Iran – pivotal for the Caspian corridor, Suez becomes ‘overcrowded’ by the new BRICS members: Ethiopia, Saudi Arabia and Egypt are practically Red Sea’s littoral states while the last one is the Canal’s (solo) proprietor.

In the early mentioned The Geography of Peace, Spykman highlighted some gateways or obligatory passages – the so-called “Gates to the Heartland” – potentially dangerous for “world peace”, from which the Russian giant (be it of that time or present day) could try to get out. In his vision, the gates are the Arctic route (the ancient Pomor Trade), the Crimea, central European plains, Caucasian passes, the Khyber Pass. Preventing access to Russia at these points is a guarantee of peace – actually of the British domination of that time.

The northern road remains accessible for Russia even if less safe after Finland entered NATO; precisely, the war against Finland (1939-1940) finished with the conquest of the Karelia region and the Rybačij Peninsula to protect Leningrad and Archangel port. The post-1989 NATO advance – past Gorbatchov’s unilateral retreat, has made Russian penetration towards central Europe almost impossible at this stage. Finally, Russia’s returned to the war to protect the Crimea and the Azov Sea (now its ‘inner sea’) as well as it (re-)appeared in Syria and the Sahel, past the West’s disastrous politico-military meddling in the MENA during its decades of ‘unipolar moment’.

By implementing the International North-South Transport Corridor, always following Spykman’s vision, which represents a route that crosses the Caucasus and the Caspian Sea, Russia, is finding a way to break the isolation up, reaching the “gates”.

Source: Arctic, Bajrektarevic, 2010

If this would be one of the world’s best concretizations of the grand Bandung and Belgrade visions of our times, the following years will certainly show us.