By Branimir Jovanović, The Vienna Institute for International Economic Studies

Trump’s tariffs will hit the Western Balkans indirectly, through reduced exports to the EU. Existing models suggest the fallout will be relatively mild, with GDP growth slowing by 0.4 to 0.9 percentage points. However, the current situation looks like a black swan – an unpredictable shock for which standard models offer limited guidance – meaning that the impact might be much bigger. Whatever happens, Western Balkan governments are not powerless – they have both the means and the responsibility to act and prevent a more serious fallout.

What tariffs did the Western Balkan economies get, and how were they calculated?

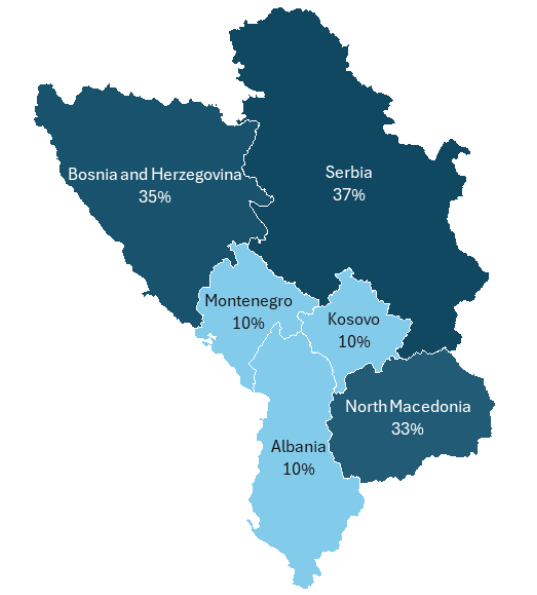

The tariffs imposed on Western Balkan economies by Donald Trump ranged widely: from 37% for Serbia, 35% for Bosnia and Herzegovina, 33% for North Macedonia, down to 10% for Albania, Montenegro, and Kosovo. Ironically, Serbia – which plans to build a Trump Tower in the centre of Belgrade – received the highest tariffs in the region from the man they intend to honour.

Chart 1 / US tariff rates to each of the Western Balkan economies

The method used to calculate the tariffs drew considerable criticism from economists. The formula was: US goods trade deficit with the country, divided by the US goods imports from the country, divided by 2. No trade economist before had used this approach.

According to US data, the United States runs a goods trade deficit with Serbia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and North Macedonia. Hence, these three countries were hit with high tariffs. The remaining three – Albania, Montenegro, and Kosovo – import more from the US than they export, so they received the minimum tariff of 10%.

But according to the national statistical offices of Serbia, North Macedonia, and Bosnia and Herzegovina, they also import more from the US than they export there. Which means that, using Trump’s own formula, they should have also received a rate of 10%.

This discrepancy stems from differences between US and Balkan trade data. This is not uncommon – much of the trade flows between these economies pass through third countries, raising questions about how such indirect trade is classified at each side.

How much do the Western Balkan economies export to the US and the EU?

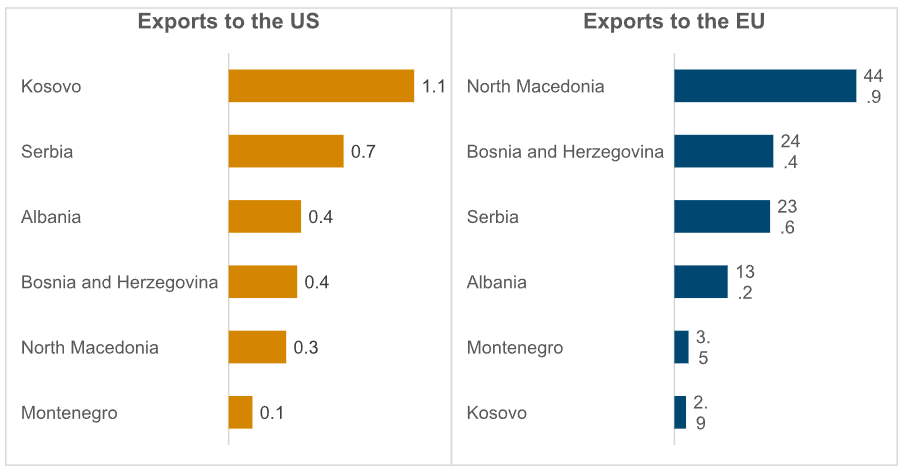

But the tariffs imposed by the US will be the least of the problems for Western Balkan economies – simply because their exports to the US are limited. Even in Kosovo, which has the highest export share to the US relative to the size of its economy, the figure is just 1.1% of GDP. In all other countries of the region, US exports account for less than 1% of GDP.

Chart 2 / Goods exports of the Western Balkan economies to the US and the EU in 2023 (in % of GDP)

By contrast, exposure to the EU market is far more significant – and far more worrying. In North Macedonia, exports to the EU reach nearly half of GDP. Bosnia and Herzegovina and Serbia are only slightly “better off,” with EU exports amounting to around one quarter of GDP. In Albania, this share is about 13%, while in Montenegro and Kosovo, it is around 3% of GDP, which is still much higher than their exports to the US.

This means that the Western Balkans will feel the impact of the trade war indirectly, through reduced exports to the EU, whose own exports are expected to decline due to high exposure to the US market and the newly introduced US tariffs – of 25% on the automotive sector, steel and aluminium, and 20% on other goods.

For the manufacturing economies – Serbia, North Macedonia, and Bosnia and Herzegovina – the main channel of impact will be reduced goods exports to the EU, especially in automotive-related industries, which have recently taken on an outsized role in these economies.

For the tourism-dependent economies – Albania and Montenegro – the trade war may result in fewer EU tourists, as households in EU countries face lower incomes and higher uncertainty.

For the whole region, including Kosovo, a third channel is likely: a decline in FDI, driven by increased global uncertainty and a deterioration in the outlook for EU-based investors – who remain the main source of FDI in most of the region.

How much will the EU suffer – and what does that mean for the Western Balkans?

The key question, then, is how much the EU itself will suffer from the newly imposed US tariffs. Colleagues at my institute have recently run a series of simulations – including this one and this one – and most estimate the impact on EU GDP to be around 0.4–0.5% per year. In other words, if previous forecasts expected EU GDP growth of 1.2% this year, the new estimate, factoring in the trade war, is closer to 0.7%.

What does this imply for the Western Balkans? To get a rough estimate, I ran a simple linear regression, relating GDP growth in each of the WB6 economies over the past 25 years to EU GDP growth. The results (shown in Table 1) were surprisingly consistent: for five out of six countries, the regression coefficient is around 0.8–0.9. This means that when EU growth slows by 1 percentage point, WB6 growth typically slows by 0.8–0.9 percentage points.

The only exception is Montenegro, which shows a much stronger sensitivity – with a coefficient of 1.9. This is due to its small size and heavy dependence on tourism, making it especially vulnerable to external shocks. A clear example is the COVID-19 pandemic, when Montenegro experienced the sharpest GDP decline in Europe. While the EU economy contracted by about 6% in 2020 and the average WB5 by around 4%, Montenegro’s GDP fell by 15%.

Table 1 / Relationship between growth in the Western Balkans and growth in the EU

| AL GDP | BA GDP | ME GDP | MK GDP | RS GDP | XK GDP | |

| EU GDP | 0.78*** | 0.91*** | 1.88*** | 0.71*** | 0.81*** | 0.78*** |

| (0.16) | (0.13) | (0.22) | (0.17) | (0.20) | (0.21) | |

| Constant | 2.95*** | 1.68*** | 0.23 | 1.54*** | 2.13*** | 3.26*** |

| (0.451) | (0.35) | (0.61) | (0.46) | (0.57) | (0.56) | |

| Observations | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 24 |

Note: Results of simple linear regressions, regressing annual real GDP growth in the Western Balkan economies, to the annual real GDP growth in the EU. Regressions were estimated over the period 2000-2024.

*** indicate significance at 1% level of significance.

Applying these coefficients to the current shock: if EU growth slows by 0.5 percentage points due to Trump’s tariffs, then Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Kosovo, North Macedonia, and Serbia can be expected to slow by around 0.4 percentage points. Montenegro, however, may experience a slowdown of nearly 0.9 percentage points.

Are we seeing a black swan?

These effects may not seem dramatic at first glance. But it’s crucial to remember that the available simulations are based on models, data, and theories developed during decades of trade liberalisation – a period characterised by rising global trade and declining tariffs. What we are seeing now is the exact opposite. Trump’s tariffs can thus be seen as a kind of black swan – a highly unusual shock for which our existing tools are poorly suited.

This also means that risks are clearly tilted to the downside. The actual economic slowdown could be much stronger than current models suggest.

The first source of risk comes from retaliation by trading partners, primarily China and the EU. China has already responded with a blanket 34% tariff on US goods. The EU has yet to act, but reports suggest that a strong and coordinated response is likely. Some expect that the EU’s reaction will not be limited to tariffs, but may target major US service sector firms, given that the US exports far more services to the EU than it imports. Such a move would almost certainly provoke further escalation from the US – raising tariffs further and possibly taking other measures. That, in turn, could lead to a new round of countermeasures from both China and the EU.

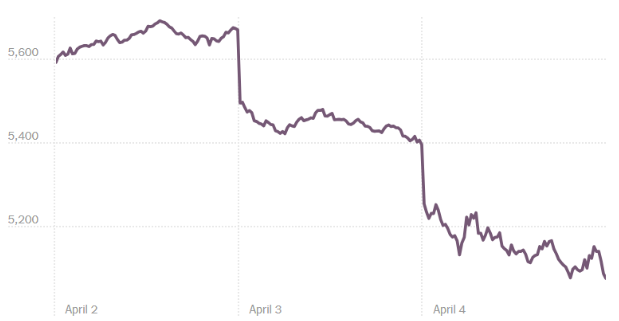

A second, and perhaps more worrying, source of risk lies outside the scope of traditional trade models. Just in the first two days after Trump’s announcement, the US stock market lost about 10% of its value – the largest drop since the COVID-19 pandemic. In absolute terms, just the 500 companies in the S&P 500 index lost over USD 5 trillion in market value – more than 20% of US GDP. Economists are now increasingly predicting that the US will enter a recession this year.

Of course, markets might recover in the coming days – or they might fall even further. But what this clearly illustrates is the uncertainty, the volatility, and the unpredictability of the fallout.

Chart 3 / S&P 500 index in the two days after the announcement of the new tariffs

Source: New York Times

What should Balkan governments do?

It’s already become something of a cliché, after so many crises in recent years, to quote Churchill’s line: “Never let a good crisis go to waste.” But for the Western Balkan governments, this moment should truly serve as a wake-up call – an opportunity to confront and address some of the long-standing structural weaknesses that continue to leave their economies vulnerable to external shocks.

First, it’s time to reduce overdependence on a single market or a single industry – even if that market is the EU or that industry is automotive. Diversifying export destinations, including greater focus on regional partners, the Middle East, North Africa and other fast-growing markets, could provide a buffer in situations such as this one. Equally important is diversification into new industries – particularly those with higher value added and greater finalisation of products, which are usually less sensitive to global shocks.

Second, the existing growth model – heavily reliant on FDI and low-cost labour – needs a reset. There is an urgent need to shift towards an innovation-driven model, built on domestic firms, supported by a coherent and proactive industrial policy.

In the short run, governments must look to kick-start other drivers of growth beyond exports. That means boosting domestic consumption, for instance through higher wages, and using fiscal policy more effectively to increase public investment, particularly in infrastructure and green transition projects, which can deliver both short-term stimulus and long-term resilience.

This crisis may have originated far away from the Western Balkans, but the Western Balkan governments are not powerless – and they can indeed do a lot to prevent the fighting elephants from destroying their grass.

/ Argumentum.al